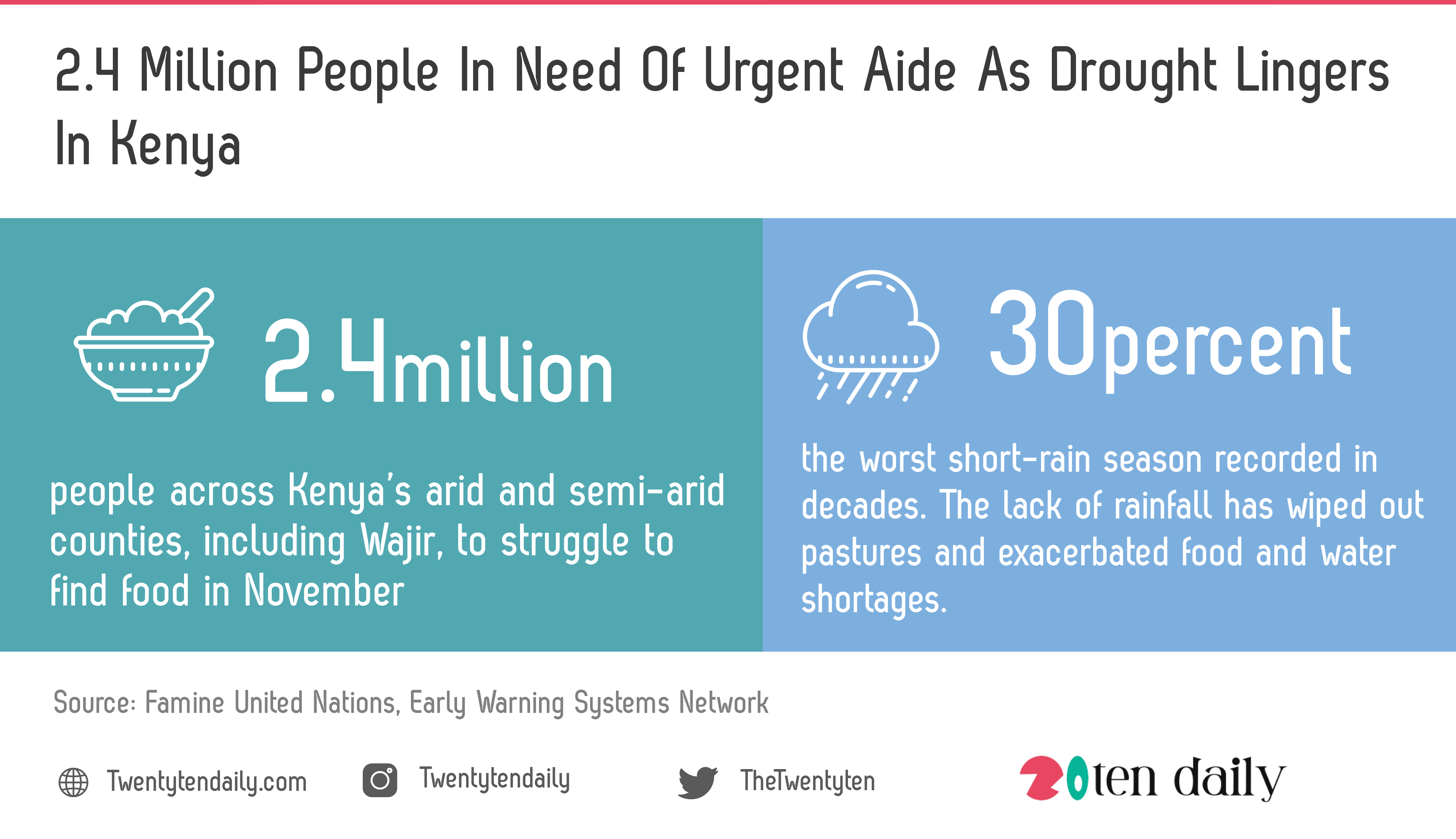

Since September, much of Kenya’s north has received less than 30 percent of normal rainfall – the worst short-rain season recorded in decades, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. The lack of rainfall has wiped out pastures and exacerbated food and water shortages.

Last month, the United Nations said it predicted about 2.4 million people across Kenya’s arid and semi-arid counties, including Wajir, to struggle to find food in November – up from 1.4 million that was recorded in February.

James Oduor, director of Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) told news correspondents that women and children have as often seen, suffered the most from the prolonged absence of rain.

With more than 465,000 children and 93,000 pregnant and breastfeeding women in Kenya’s affected regions, reports share that more than half of the vulnerable population are already acutely malnourished, with toddlers suffering from frequent diarrhoea.

Is there a way out?

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2020 ranked as the third-warmest year ever recorded in Africa. Estimates suggest the temperature could rise by up to 2.5C (4.5F) by 2050. Experts say that for every increment of global warming, changes in extreme weather events become larger. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moist air that can lead to extreme rainfall, but it can also result in more evaporation which brings more intense droughts.

The NDMA’s Oduor said, in northern Kenya, climate change is part of the problem, but other factors such as population growth, landscape modification due to agricultural irrigation and settlement expansions have also worsened the effect of droughts.

“In semi-arid regions, you used to have vast areas not occupied, where pastoral communities could move around – now that movement is curtailed and bigger communities are growing in smaller places,” he said.

The shortage of resources has a domino effect on local communities, leading to rising tensions over the control of grazing land, as well as higher prices and more students dropping out of school to follow their family’s cattle to more remote areas in search of water.

Oduor said only long-term sustainable development projects could contain the effects of droughts in Kenya’s north.

“Reversing a drought is almost impossible, but you can make people cope with it,” he said while citing solutions like the construction of additional water and health infrastructure, as well as less dependency on farming and livestock rearing for income.