First detected in South Africa, the B.1.351 of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has spread to dozens of countries around the world.

Fact Check

The B.1.351 is not a different virus.

As the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads around the world, it constantly mutates which leads to the emergence of new strains. The B.1.351 is a variant of the coronavirus.

The South African variant

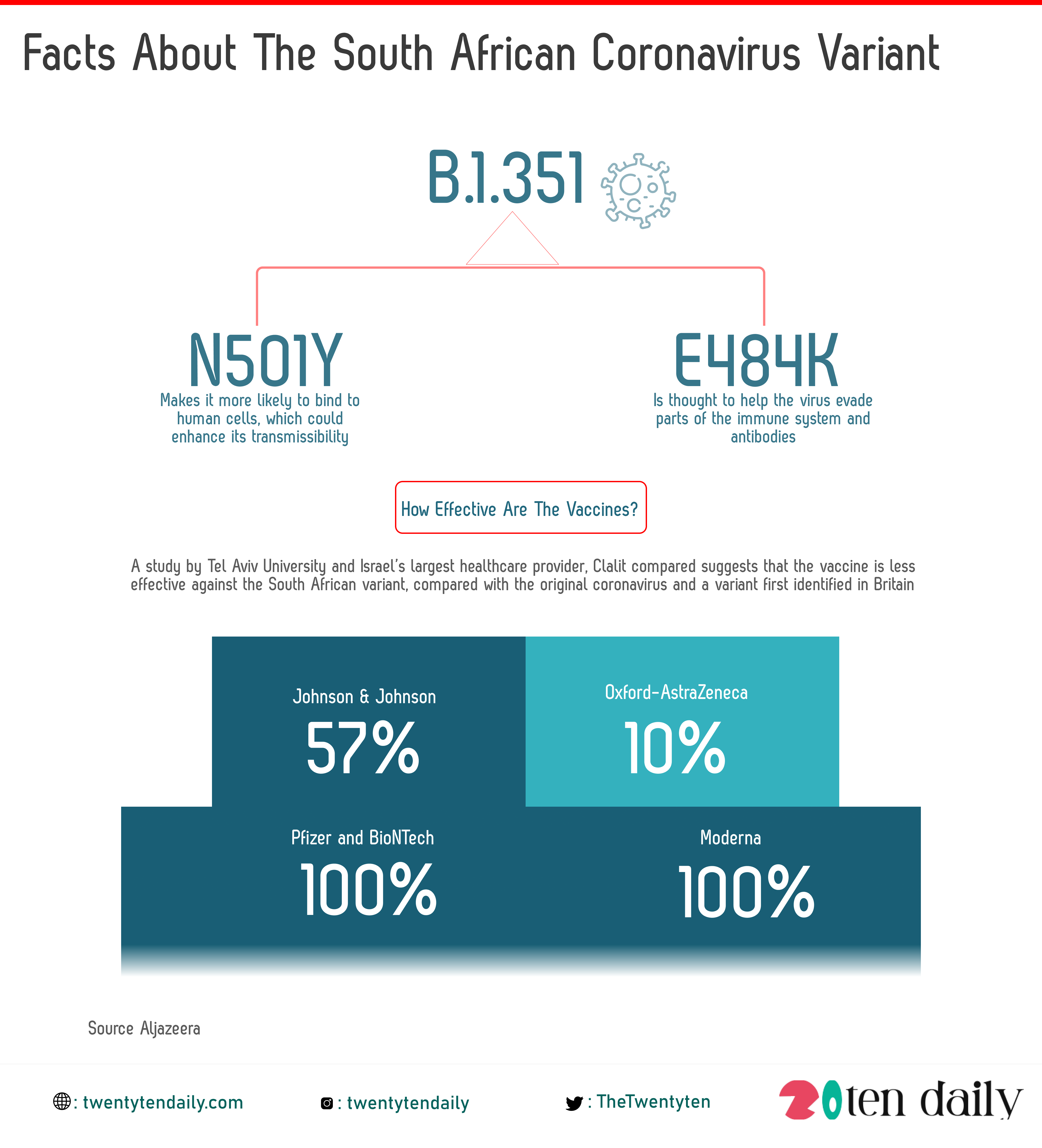

First discovered late last year in South Africa, the B.1.351 contains two mutations that have raised concerns of it being more infectious than previous strains of the virus which might be able to evade some of the antibody response caused by vaccines or previous infections.

The first, known as the N501Y mutation, makes it more likely to bind to human cells, which could enhance its transmissibility. It also has the E484K mutation, which is thought to help the virus evade parts of the immune system and antibodies.

A report by the World Health Organization showed that preliminary studies suggested the variant was associated with “a higher viral load, which may suggest the potential for increased transmissibility, this, as well as other factors that influence transmissibility, are subject of further investigation”.

“Moreover, at this stage, there is no clear evidence of the new variant being associated with more severe disease or worse outcomes,” the WHO said.

Can Available Vaccines Work Against The Variant

At the time of the variant’s emergence, experts expressed worry that the available vaccines might not be effective to combat the B.1.351, now, a real-world study has confirmed these fears.

The study discovered that the variant can “break through” Pfizer-BioNTech’s coronavirus vaccine to some extent.

The study by Tel Aviv University and Israel’s largest healthcare provider, Clalit compared almost 400 people who had tested positive for COVID-19, 14 days or more after they received one or two doses of the vaccine, against the same number of unvaccinated patients with the disease. It matched age and gender, among other characteristics.

The South African variant was found to make up about one percent of all the COVID-19 cases across all the people studied.

However, among patients who had received two doses of the vaccine, the variant’s prevalence rate was eight times higher than those unvaccinated – 5.4 percent versus 0.7 percent.

This suggests the vaccine is less effective against the South African variant, compared with the original coronavirus and a variant first identified in Britain that has come to comprise nearly all COVID-19 cases in Israel, the researchers said.

“We found a disproportionately higher rate of the South African variant among people vaccinated with a second dose, compared to the unvaccinated group. This means that the South African variant is able, to some extent, to break through the vaccine’s protection,” said Tel Aviv University’s Adi Stern.

The researchers cautioned that the study only had a small sample size of people infected with the South African variant because of its rarity in Israel.

They also said the research was not intended to deduce overall vaccine effectiveness against any variant, since it only looked at people who had already tested positive for COVID-19, not at overall infection rates.

Pfizer made no immediate comment on the Israeli study, which has not been peer-reviewed.

Earlier this month, Pfizer and BioNTech said clinical trial data signalled that their COVID-19 vaccine could protect against B.1.351. In a trial with some 800 participants in South Africa, a relatively small number, the companies found that the shot was 100 percent effective in preventing illness.

For the Moderna vaccine, the company producing it said in late January that its vaccine was effective against the South African strain.

Moderna said there was a six-fold reduction in neutralising antibodies produced against the South African variant, the levels remained above those that are expected to be protective.

A trial of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine, which was made in partnership with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, found it was about 85 percent effective in protecting against severe cases of COVID-19, and 57 percent effective against all forms of the disease.

While the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine offers as little as 10 percent protection against the variant, researchers have suggested.