India crossed a grim milestone in April when it recorded the supposed highest daily tally of new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the world with 360 960.

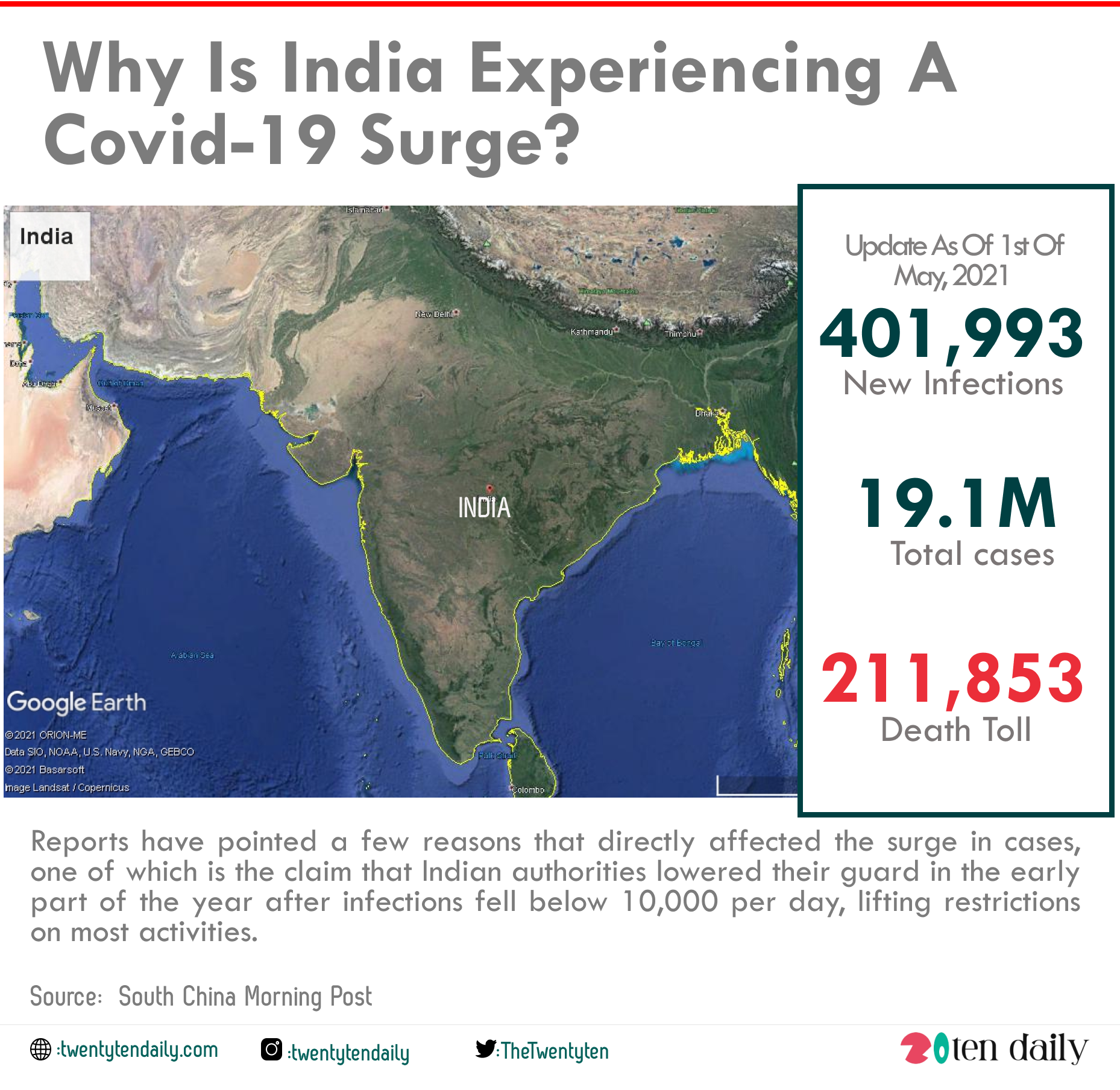

Unfortunately, on May 1, the ministry of health in India announced 401,993 new infections, taking its pandemic total to 19.1 million cases, second only to the US, with a death toll of 211,853.

The escalating daily surge in the virus has caused countries to temporarily shut their gates to India to fear a possible spread. On the other hand, experts have asked meaningful questions on the real reason behind the sudden surge in the Covid-19 cases in India.

What Is Causing India’s Second Wave?

Reports have pointed a few reasons that directly affected the surge in cases, one of which is the claim that Indian authorities lowered their guard in the early part of the year after infections fell below 10,000 per day, lifting restrictions on most activities.

Mass religious gatherings such as the Kumbh Mela, attracting millions of Hindu pilgrims, and political rallies were allowed to continue even when cases numbers began rising sharply in late March.

In some of the most badly hit states, like Delhi and Maharashtra, community transmission became very rampant as people took social distancing and mask-wearing with laxity.

Another cause to point out is India’s low testing rates. A report published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases in December 2020 advised that a lockdown was only a temporary measure to quell outbreaks shortly after transmission rate’s significant fall during the first lockdown in India. The authors recommended ramping up testing and self-isolation to prevent secondary infections, yet India’s testing rate remains among the lowest in the world. Comparisons are difficult, as India doesn’t release daily test numbers for the country as a whole, but the health ministry said that a total of 1.75 million samples had been PCR tested as of April 27. The UK performs 500 000 PCR tests every day.

There is also India’s very fragile health infrastructure.

On 11 May 2020, soon after the first lockdown was lifted, a government’s policy analysed the country’s covid-19 response and found a severe dearth of medical equipment such as the testing kits, PPE, masks, and ventilators. It also noted the long-running shortage of emergency healthcare and lack of professionals: the ratio of doctors to patients was recorded as 1:1445 and of hospital beds to people 0.7:1000, with a ventilator to population ratio of 40 000 to 1.3 billion.

In the latest crisis, medical supplies and oxygen are being shipped in from 15 countries and international aid organisations such as Unicef. Devi Prakash Shetty, a cardiac surgeon and chairman and founder of the Narayana Health chain of medical centres, has estimated that India would need about 500 000 ICU beds and 350 000 medical staff in the next few weeks. At present it has only 90 000 ICU beds, almost fully occupied

Can A New Variant Be Blamed?

The South African B.1.351 also known as 20H/501Y, Brazil’s (P.1), and the UK (B.1.1.7) have all been found in circulation in India, alongside a newly identified distinct Indian variant (B.1.617) first identified in October.

These variants can be factors that has affected the surge in cases, but the extent of involvement of each is as yet unknown.

“The B.1.617 variant has spread rapidly in parts of India, apparently dominating over previously circulating viruses in some parts of the country,” said Ravi Gupta, professor of clinical microbiology at the University of Cambridge, who is studying these variants. “B.1.1.7 is dominating in some parts, and B.1.617 has become dominant in others, suggesting both may have an advantage over pre-existing strains.”

Scientists are concerned about two mutations in B.1.617 (E484K and L452R), which have led it to be dubbed a “double mutant.” Gupta said that the L452R mutation is in a key area of the spike that is recognised by antibodies after vaccination or infection. E484K also has this effect. “The worry is that the two may have additive effects in making the virus less sensitive to antibodies,” he said, though adding that this is just a possibility at this stage, with no confirmation.

The Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genomics Consortium (INSACOG), a group of 10 national laboratories, was set up in December 2020 to monitor genetic variations in the coronavirus, particularly B.1.1.7, but the lack of testing and sequencing capacity is hindering efforts. Government data show that India has sequenced less than 1% of its positive samples, whereas the proportion is 4% in the US and 8% in the UK.