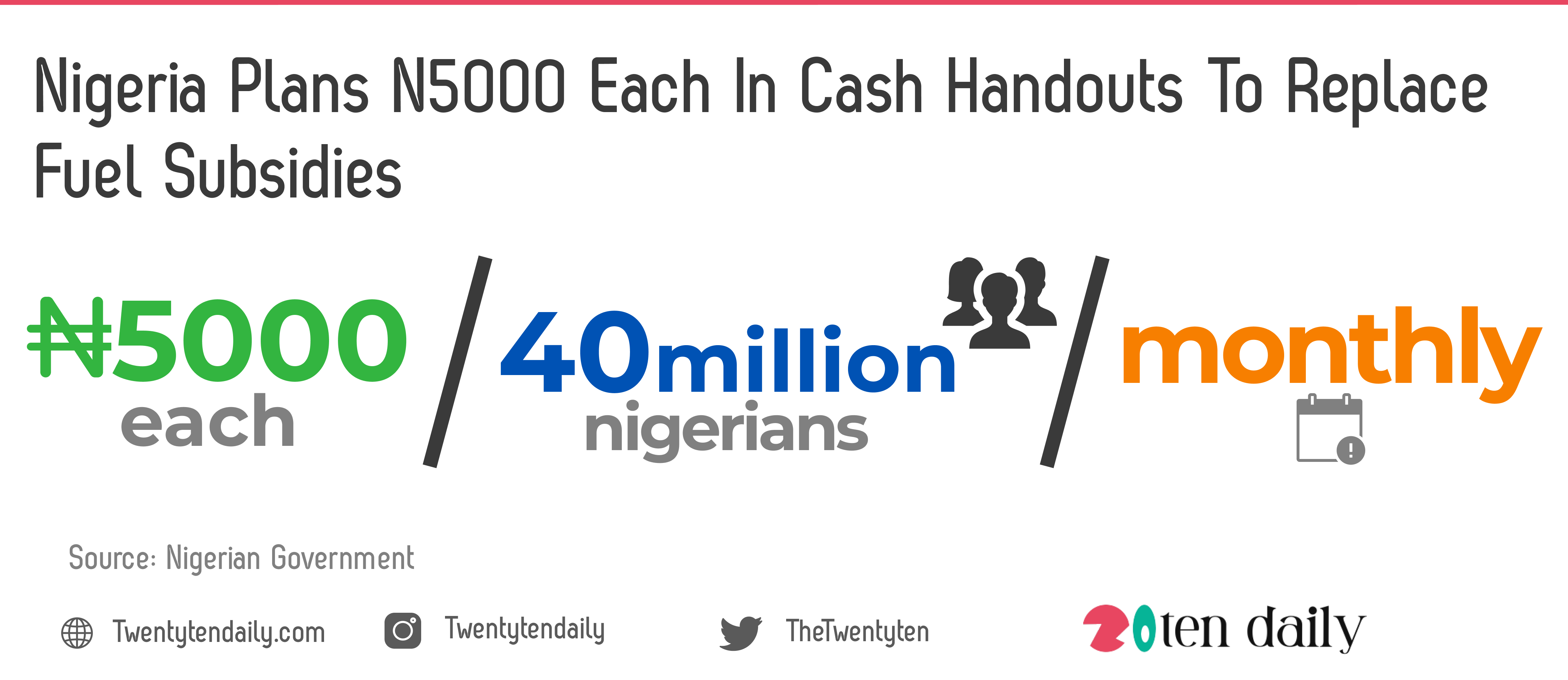

The Nigerian government is planning to replace fuel subsidies in 2022 with cash handouts of up to N5000, an amount that would cost the country up to 2.4 trillion naira in a year.

According to Finance Minister, Zainab Ahmed, the government will give 5,000 naira each to as many as 40 million people every month, beginning from July when fuel subsidies end. A new petroleum law compels the government to allow market forces to determine gasoline prices. The cash transfers will happen for six to 12 months.

The government will make sure that the payments go to the rightful recipients by using biometric verification numbers, national identity cards and bank account numbers, Ahmed said last week. It is working with the World Bank to design and fund the plan.

Nigeria wants to scrap fuel subsidies because the nation’s budget can no longer contain the financial burden. The subsidies will drive budget shortfall to 6.3% of economic output this year, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The subsidies currently cost the government about 250 billion naira a month, Ahmed said. The IMF recommended that the West African nation do away with the subsidies and implement a “well-targeted social assistance plan” to cushion the negative impact of cutting subsidies on the poor.

Africa’s most populous country hosts the world’s largest number of people living in extreme poverty, living on income as low as about $1.90 a day. The monthly grant would therefore be a significant boost in income for such people.

Still, the 2.4 trillion naira a year cost could become a big burden and President Buhari’s successor may be saddled with the decision of extending or ending it.

The West African nation does not have a good record of taking politically difficult decisions. It has struggled for decades to end fuel subsidies, which is expected to cost 3 trillion naira over the next 12 months if oil prices remain at current prices. In addition, it has been unable to end electricity subsidies.

Cash support programs have helped the poor from Togo to India but in a nation where few have bank accounts, the process may lead to corruption, said Cheta Nwanze, a lead partner with SBM Intelligence.

“I would have preferred such grants go to small businesses so they can expand and put a dent in our rather high unemployment rate,” Nwanze said.