A new coronavirus variant has been identified in South Africa referred to as the C.1.2 variant. Though not yet classified as a variant of interest or concern by the World Health Organization (WHO), the variant is drawing the attention of scientists due to the number and types of mutations it contains and the speed at which the mutations have occurred.

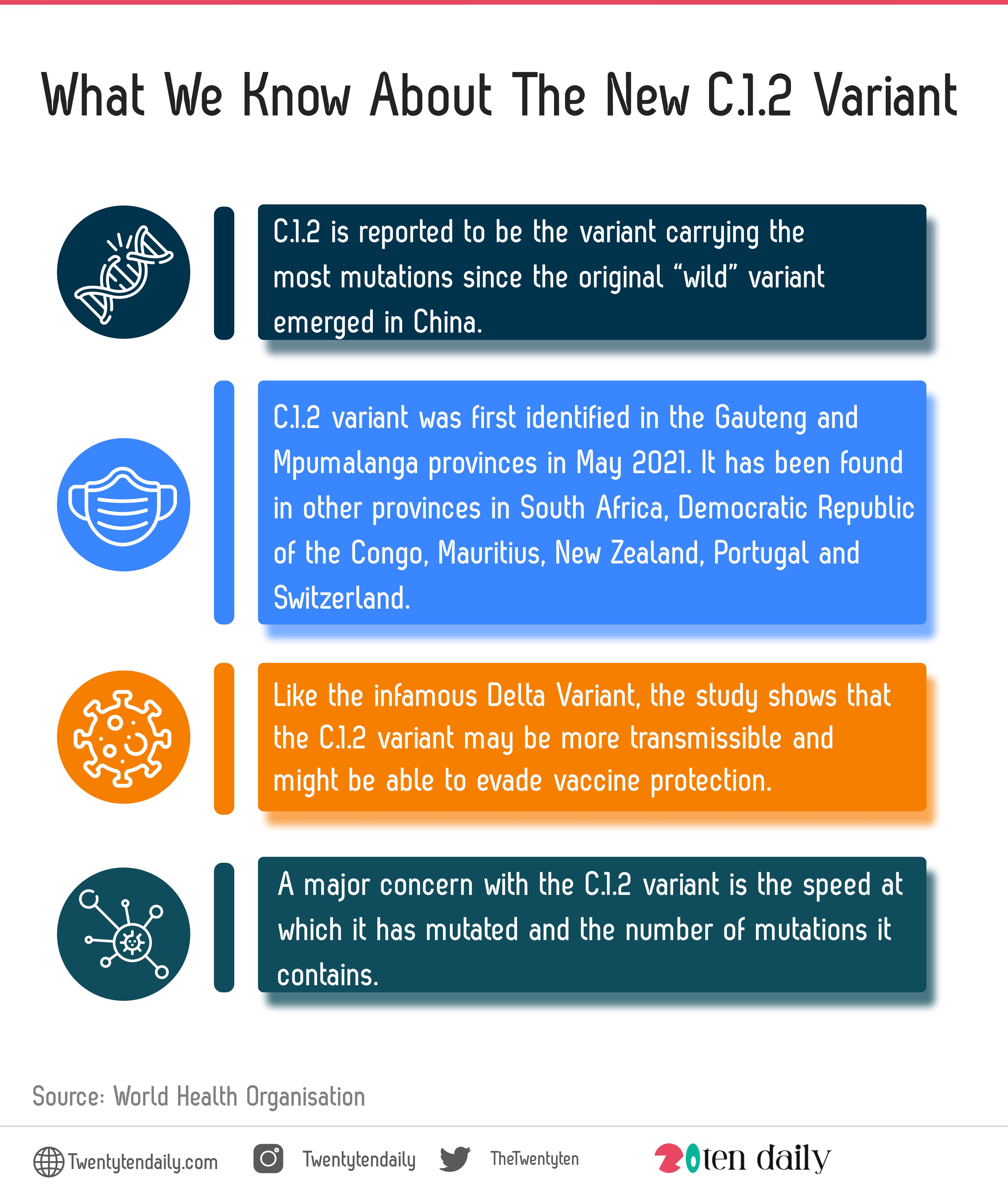

C.1.2 is reported to be the variant carrying the most mutations since the original “wild” variant emerged in China.

According to a pre-print study put out by South Africa’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases, the C.1.2 variant was first identified in the Gauteng and Mpumalanga provinces in May 2021.

It has been found in other provinces in South Africa as well as in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mauritius, New Zealand, Portugal and Switzerland.

Like the infamous Delta Variant, the study shows that the C.1.2 variant may be more transmissible and might be able to evade vaccine protection. This conclusion has not been peer-reviewed.

Mutations are part of the course of many viral diseases that spread as quickly as the coronavirus. The more people the virus infects the more likely it is to mutate. When the coronavirus enters a human cell its main job is to instruct the cell to make more copies of the virus; these then leave the cell and infect other cells in their human host. The process of viral replication is relatively fast and errors can be made in the copying of viral DNA – these are known as mutations.

Most mutations are either harmful to the virus, and that particular virus dies out quickly, or confer no benefit at all. But now and again a mutation that is advantageous to the virus will randomly occur – be it making it more transmissible or even making it partially resistant to vaccines.

A major concern with the C.1.2 variant is the speed at which it has mutated and the number of mutations it contains. Another reason scientists want to monitor C.1.2 closely is that some of these mutations look similar to those that have helped the Delta variant become the dominant strain across the world, while others align with what we have seen previously with the Beta variant. Any time these mutations are seen in a new variant it is important to keep an eye on how it spreads and what it does.

Although levels of the C.1.2 variant are still low among the South African population, it remains a concern to local public health experts and scientists across the world. The variant has emerged from the C.1 lineage which was one of the coronavirus lineages that dominated during the first wave of infections in South Africa in mid-May 2020.

Currently, Delta remains the dominant variant in South Africa and much of Africa. For the C.1.2 variant to become dominant it will have to outcompete with Delta. That will mean increased transmissibility, being able to bind to human host cells and infect people quicker than Delta currently does. Scientists refer to this as a virus’s “affinity” – how well it can grab onto and enter human cells; C.1.2 will have to have a better level of affinity than Delta to become dominant.

The bottom line is that it remains to be seen whether C.1.2 is indeed more transmissible than Delta or if it can partially evade the immune response triggered by the vaccine or previous infection. It will take time and detailed laboratory studies to confirm the types of mutations C.1.2 harbours and any advantages they may confer. What remains important and certain is that vaccinations are still the best way to protect against serious symptoms of COVID-19 and reduce the number of deaths that are still occurring worldwide from this disease.